alva is now Penta. We are the world’s first comprehensive stakeholder solutions firm. Learn More

Hit enter to search or ESC to close

Despite having access to more information than ever before, people appear to be suffering from an information paradox: as access to information increases, the ability to parse and interpret that information for truth wanes. Apparent 5G-health misinformation is just the latest focus in an era of social media-induced misinformation. As the globe battles a deadly pandemic, the time for misinformation couldn’t be worse – or more threatening to our recovery.

The rise of misinformation has tracked closely with the expansion of social media and the digitalisation of the global economy. In just the last several weeks, Facebook has faced fresh allegations of rampant misinformation about Covid-19 on its platform, the US presidential election has been mired in legal disputes over ‘alternative facts’ and so-called anti-maskers are beginning to merge with anti-vaxxers, setting up a potentially deadly showdown.

What is driving this broad distrust and increasing misinformation in our world?

Well, for one, we are increasingly reliant on social media and the internet for news and information. According to Ofcom, roughly 50% of all UK adults use social media for their primary source of news. And for this reason, academics and regulators have long warned of a coming ‘information disorder’ – an instance in which the public cannot parse through large amounts of information without being influenced by false information.

Second, we spend less time validating and reading widely on a subject, limiting our ability to engage alternate viewpoints. Increasingly, users self-select into ‘echo chambers’ of those who think alike, tending to pass on rumours and fake news that substantiate their point of view, which in turn, further magnifies polarisation and belief in misinformation.

Third, in this moment, many of us are holed-up at home as the pandemic rages on. Many have retreated from traditional media since March, with UK national publications losing 3 million daily digital readers after Q2. In this time, people have used social media more than ever to stay connected. But, apparent misinformation is spreading like wildfire through social networks. So, what happens when tools meant to connect divide us instead?

Just about any newly introduced technology could face backlash from consumers. Look and you can see this all around us in today’s world: from wind farms to 5G technology. We will use the latter as a lens to better understand why misinformation has become so problematic.

Since cellular technology first emerged several decades ago, the public has often wondered aloud, without much scientific evidence, whether cancer or infertility would be side effects of the technology. So far, they haven’t.

Since then, telecommunications companies have invested billions in building the infrastructure that would eventually support 5G and the technological advances it promises.

But as 5G came into our lexicon, so too did rumours that the fifth-generation mobile technology was bad for human health. Then along came Covid-19.

Suddenly, social media was awash with 5G conspiracy theories. It didn’t matter where you looked – Facebook, YouTube, or Twitter. The words were slightly different but sang the same tune: “Wuhan was the first city to launch 5G” or “Former Vodafone Boss Blows Whistle On 5G.” The UK’s Rapid Response Unit, a sort of cyber command centre set up to deal with coronavirus misinformation, reports that it deals with up to 70 such incidents a week – on Covid-19 alone!

But from here things got strange. Well, stranger.

As the 5G-Covid-19 rumors began bouncing around social networks, some users found themselves so afraid of the next generation mobile technology that they began destroying telephone masts, usually through arson. Since March, a sharp increase in vandalism against telecommunication infrastructure has resulted in more than 150 arson attacks on 5G masts throughout Europe, with the highest number occurring in the UK (77).

Worse still, UK-provider BT reports that nearly 40 incidents have been recorded wherein a member of the public has assaulted or threatened engineers carrying out essential works. 5G has inspired such powerful anger and fear that human lives are now being put in peril in addition to critical infrastructure.

These attacks amount to untold millions of lost investments for telecommunications firms and delays to integration of IoT brought about by 5G. This 5G and health misinformation is not yet dissipating. If anything, its grip has tightened since early 2020.

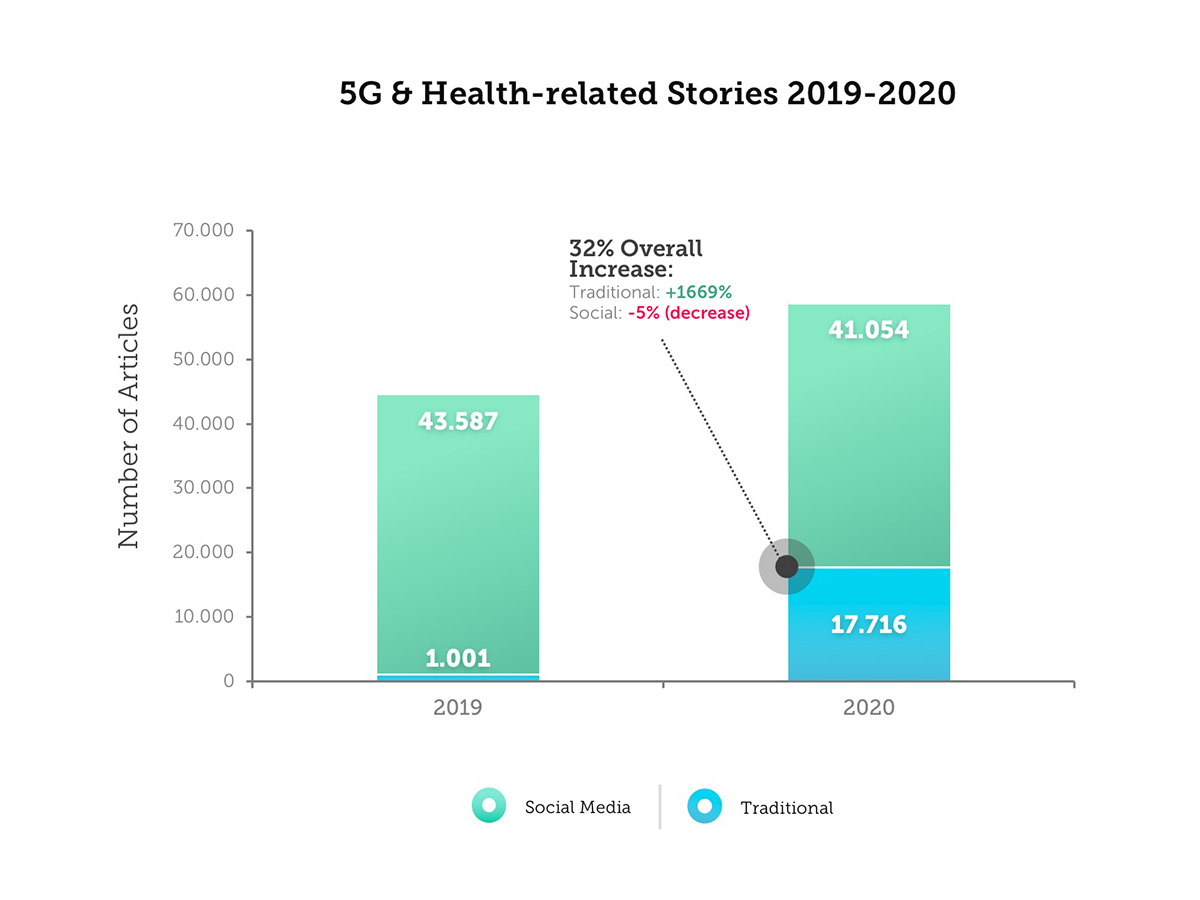

Graph 1: Volume by Year on link between 5G and Health Issues (2019-20)

In February, alva analysed data to determine what was driving the link between 5G and health-related stories, especially cancer. We found that year-on-year coverage had jumped from just 24 traditional media articles per-month on the link in January 2019 to 131 in January 2020.

However, in our most recent analysis, we find that articles linking 5G to cancer dropped off in early March and are now nowhere to be found. Instead, these stories have been reincarnated as a purported link between 5G and Covid-19.

To better see this, we separated data from social media from traditional media – the 5G controversy began online, after all. What we found demonstrates the power of social media to influence those who may not have accounts of their own but who could be influenced by reports in traditional media (see Graph 2).

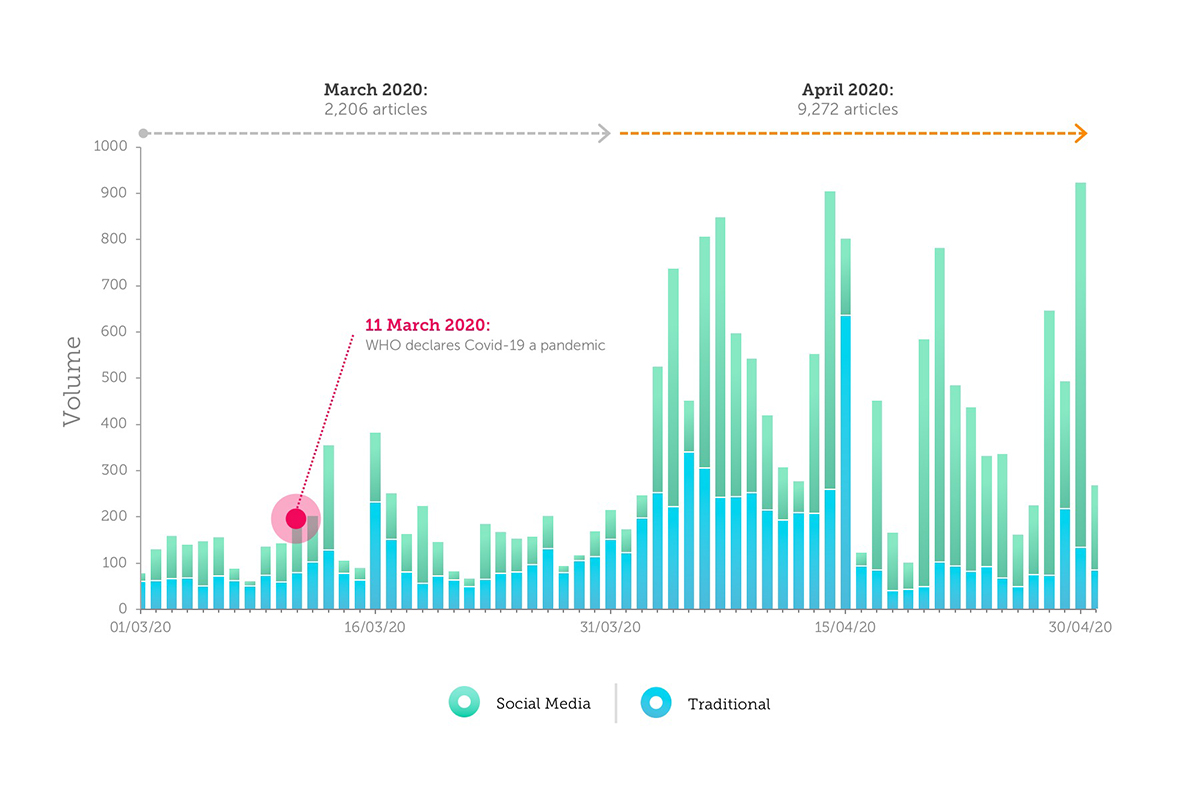

Graph 2: Volumes by Day on link between 5G and Health Issues (2020)

In 2019, 5G-health stories were mostly social media-led, with more limited pick-up in traditional outlets. Of traditional outlets, regional publications were the most likely to publish stories on an alleged 5G-health link. By early 2020, we see much of the same: minor discussion, almost theoretical in nature, on the links between 5G and health, mostly led by sensational social media posts.

That is, until, the world changed.

Around the time that the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 a pandemic, the number of articles linking 5G with the coronavirus begins to skyrocket. In April alone, there are over are over 5,000 traditional media articles on the subject – that’s up from just under 200 traditional articles in April 2019.

Whereas 2019’s 5G-health stories were primarily social media driven, 2020 tells a different story. By mid-March, other traditional publications, including national and wire-based outlets, were widely publishing stories on a purported link between 5G and adverse health impacts.

Overall coverage is up +32% year-on-year, with traditional publications seeing +1,699% increase from 2019 – and 2020 isn’t even over yet!

But it’s not just traditional media, social media is what gave the new 5G-Covid-19 story legs. Social media coverage is on par with 2019, and looks likely to match or eclipse last year’s levels of coverage. As such, it is imperative to understand how social media stories can influence coverage in national and local outlets, which arguably are more persuasive to readers than tweets or posts from the tin foil brigade.

As you can see in Graph 2 above, social media stories highlighting the link between 5G and Covid-19 tend be short-lived and highly visible. After the WHO declared Covid-19 a pandemic on 11 March, we suddenly see a sharp rise in social media chatter about alleged links between 5G and the disease. In fact, we see that social media actually drives traditional media coverage to its highest levels to-date.

This is the current landscape for communicators. Society’s ‘information disorder’ could yet get more fevered as job cuts mount, protests continue, climate disasters unfold and elections are contested. At the end of the day, the 5G-health controversy is a human-enabled falsehood that spreads when the public’s attention is elsewhere. The more ‘stressors’ added into the mix, the greater the opportunity for societal disquiet to emerge.

As 5G communications strategies continue to be refined, communicators should consider the following to enable success:

There is reason for hope. People have always adapted to change and there is no reason to believe that this current wave of challenges will be insurmountable. The important question here is to determine what kind of problem online misinformation is. Is it something that can resolved and “fixed” quickly? Or is it more like a social condition, something that requires constant tweaking and constant maintenance and vigilance by us all. The evidence point incontrovertibly towards the latter.

Be part of the Stakeholder Intelligence community