alva is now Penta. We are the world’s first comprehensive stakeholder solutions firm. Learn More

Hit enter to search or ESC to close

It seems barely possible to open a newspaper (as outdated a notion as that might seem) these days without reading about an organisation facing a risk to its reputation. The phrase “reputation risk” has become entrenched in the media lexicon, acting as a shorthand for something bad that a company has done or that has befallen an organisation.

You can download the full report as a PDF here

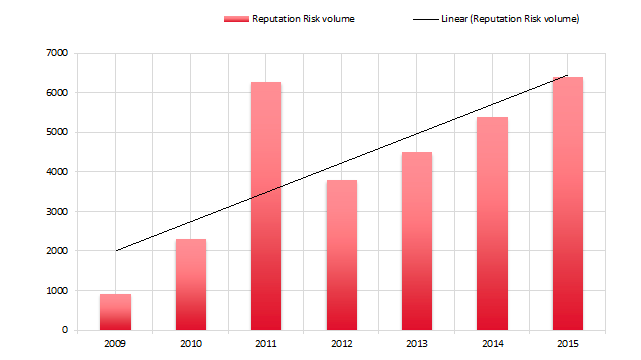

As Figure I testifies, the frequency with which “Reputation Risk” is referenced in publicly-available content, in English language and across all sources (print, online, social media, blogs, broadcast, analyst reports, trade publications, surveys, customer forums and opinion leaders) is on a steep upward trajectory.

Figure I: References to “reputation risk” in publicly-available content over time

How times have changed. When alva first started out in 2010, we used to include in our meeting pack an introduction to reputation and why companies should care about it.

Business leaders are much more attuned to the importance of reputation, and primary research on the subject reveals that reputation risk has long been acknowledged to be the key risk facing businesses.

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s pioneering 2005 paper, Reputation Risk of Risks, established Reputation Risk as the number one priority for senior risk professionals. Equally, Deloitte’s global risk survey in 2014 found that 87% of the global executives they survey rate reputation risk as “more important” or “much more important”.

This is where the picture becomes less clear. In many organisations, reputation has traditionally sat with the Corporate Affairs or Communications departments.

This situation is often a legacy of reputation historically having been seen as synonymous with public relations.

In today’s always-on, multi-stakeholder, multi-channel environment, it is not possible for reputation to be managed solely through public relations. All parts of the business which interact with stakeholders from HR through to IR are involved in building and maintaining an organisation’s reputation.

However, the reporting of reputation and reputation risk internally is not something that can be managed by all departments and in the majority of organisations, one function is charged with owning and coordinating the reporting of reputation to the board so that the relevant actions can be taken to mitigate risk and leverage opportunities.

Corporate Affairs is most often the function being asked to provide this reputation intelligence to the rest of the business*. This presents an enormous opportunity – if reputation is the biggest concern to the leadership of the business, the department which is responsible for providing reputation intelligence should see a commensurate increase in its status within the business.

However, it is not alone in appreciating the significance of reputation to the business and there is increasing evidence that other functions such as Risk itself, Legal Counsel and Marketing are either proactively seizing the reputation initiative or being asked to looking into this area by the board.

*“Staying on the front foot”, p.17, Helsby Watson

While reputation is regularly reported as contributing up to 75% of an organisation’s market value, reputation risk has its own reputation: that of being difficult, and some would say “impossible”, to quantify.

Before the rise of technology facilitated a greater interconnectedness of stakeholders, different proxies for reputation were developed based on the stakeholder in question: Investor relations would look at share price, analyst ratings and investor surveys to understand investor sentiment; HR would hold annual employee engagement surveys to understand the employee perspective; marketing and customer experience would have customer feedback surveys and Net Promoter Scores; while Communications and Corporate Affairs would rely on media analysis to take the pulse of the media and public landscapes.

These proxies were adequate measures when it was possible to neatly segregate stakeholder groups. This was because each stakeholder group had its own interests and expectations which, by and large, existed in isolation from those of other stakeholders. This enabled companies to approach these stakeholders in very different ways and indeed led to the creation of separate siloed functions to deal with them.

With the advent of digital media and communications, we have witnessed an ever-increasing interaction between stakeholder groups and a consequent greater blurring of the boundaries between the interests, expectations and needs of different stakeholders. As information becomes more freely available, this segregated model of reputation proxies using different metrics and reporting on different frequencies is no longer fit for purpose.

How, for example, can the board understand where to focus its attention and resource when it receives a monthly volume analysis to understand media performance, a daily update on share price, a quarterly net promoter score and an annual employee engagement metric? How to prioritise between these disparate measures? How to quantify what is actually a reputational risk or opportunity?

Primary research can help join up these different perspectives, using one standardised metric to help boards compare and contrast their standing with different stakeholders. However, primary research is hampered by its small sample sizes, the low frequency at which it can be conducted (quite at odds with how quickly stakeholder sentiment can shift) and ongoing concerns about the robustness of its approach, as seen in the UK General Election of 2015.

The final, and in many ways most important, aspect to consider regarding reputation intelligence is the “so what” factor. This is the biggest challenge facing Corporate Affairs’ claim to own the provision of reputation intelligence. While functions such as Risk and Marketing are used to providing evidence of the value of their activities linked to financial value, Corporate Affairs has been poorly served by their reliance on media analysis and social media analysis over the past 10-15 years.

Despite moves to standardise and improve communications measurement, the Barcelona 2.0 principles lack the robustness and credibility to be taken seriously at board level and do not attempt to address the thornier issue of quantifying the impact of a reputational risk on business KPIs.

As Nick Helsby states in a post regarding which function is leading on reputation risk in the organisation:

Reputation risk is…a major preoccupation for most boards who are looking for reassurance that reputation risk is being managed systematically, and with the same rigour and frameworks, as every other risk.

To respond to the growing requirement to report on reputation at board level, Corporate Affairs needs to be able to provide robust and credible reputation intelligence – the “rigour” and “frameworks” of Helsby’s point.

This intelligence needs to reflect the significant shifts in the reputational landscape which have occurred since the advent of digital technology.

Reputation is a multi-stakeholder concept – companies do not own their reputation and indeed they do not have one single reputation. Your reputation is what other people think and feel about you, seen through the lens of their expectations and needs.

Reputation intelligence therefore needs to reflect this multi-stakeholder and multi-channel reality by casting its net wider than one set of sources or a small sample of audience opinions.

This is the era of big data and publicly-available content provides organisations with a wealth of direct and indirect stakeholder perceptions that can be analysed and interpreted to understand shifts in sentiment for companies, issues and stakeholders over time.

This includes traditional media (print, broadcast, online and subscription sources), social media (Twitter, blogs, forums and social networks), surveys and analyst reports.

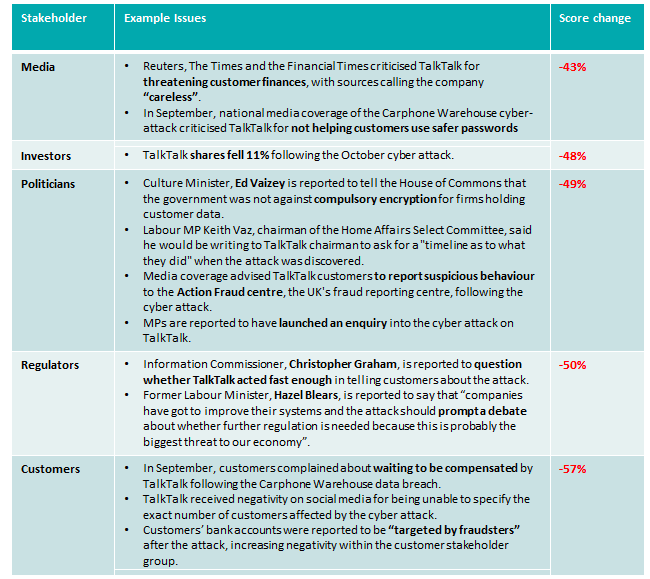

Figure II: Example monthly stakeholder analysis by issue and score

To respond to the fact that reputation is in the eye of the stakeholder, decision intelligence should be able to feed back to boards where they stand with their individual stakeholder groups, how that compares to their competitors and which issues present risks and opportunities to these stakeholders’ continued support.

This makes the intelligence decision-ready; by using one system, companies can clearly understand which groups they need to prioritise and which levers to pull to improve their standing with their stakeholders.

Figure II is an example of how stakeholder-specific analysis can be carried out for an organisation and how issues, scores and specific antagonists or advocates can be highlighted for the business to prioritise.

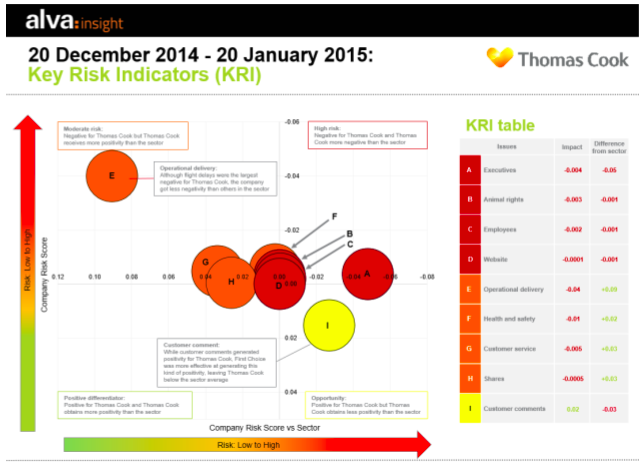

Figure III: Example Key Risk Indicator reporting – Thomas Cook

Equally to report on reputation risk, companies can employ complementary bottom-up and top-down approaches to ensure they are well covered. From a bottom-up perspective, the external drivers of current company negativity can be isolated and tracked over time as reputation risks.

Figure III gives an example of how this approach can be represented using familiar Risk reporting visual language. This enables the growth of reputation risks to be monitored and mitigation strategies to be developed.

As a build to this, horizon scanning in the form of a sector-wide or indeed issues-wide analysis of the drivers of negativity (beyond the company itself) can be conducted to understand where risks may spill over to affect the company at a later date.

The top-down corollary to this is to actively interrogate the publicly-available data for signs of the development of known risks already tracked on the company risk log. Here we can see reputation intelligence enhancing the company’s internal risk reporting by providing an outside-in perspective.

While the first part of collating robust, statistically-significant reputation intelligence resides in widening the net to include multiple stakeholder perspectives across a comprehensive set of channels, the aforementioned “so what” factor has to be answered when dealing with something as nebulous as reputation.

The best way to do this is by linking reputation to things that the business genuinely cares about, namely its Key Performance Indicators. This can be sales, share price, employee engagement or any other stakeholder-relevant metric.

What matters is being able to correlate both the impact of reputation, and by extension reputation risk, on the company’s KPIs. This is the most effective way of ensuring that reputation is understood and managed as a strategic priority at board level.

It is undeniable that reputation risk is an increasingly dominant subject both in the media and public domains, as well as in the boardroom. However, the gap between the desire to manage this risk and companies’ ability to do so is stark.

The Corporate Affairs function, as the legacy “owners” of reputation, has a golden opportunity to seize the initiative and provide the board what it needs – robust reputation intelligence – and thereby to enhance its own position and reputation in the organisation.

The risk for Corporate Affairs is that it has long been underserved on the data front meaning that Risk, Legal Counsel and Marketing may be seen as more reliable providers of robust reputation intelligence.

Whichever function is ultimately given the responsibility for reputation would be well advised to keep in mind the findings of this report and the five following key criteria for reputation intelligence:

Multi-stakeholder: To understand the various reputations a company has, reputation intelligence needs to take into consideration a wider range of perspectives. This can include Customers, Investors, Employees, Regulators, Government, Media and any other important group.

Multi-channel: Only media or social media will not give the full picture. Different stakeholders are active (and interact) across different channels, so reputation intelligence must be far-reaching in its scope.

Representative sample size: Interviews with key stakeholders remain important, but assessing how representative an issue is, as well ensuring that no risk or opportunity is missed, requires a statistically significant set of ongoing data points to understand how an issue is evolving.

Frequency of reporting: There is a balance to be struck between the need to understand the broader trends and to mitigate reputational risks as these emerge. Once or twice a year is no longer adequate or reflective of the pace of change.

Link to business KPIs: Reputation has long been seen as a “fluffy” concept, but it can and should be grounded in both the language and objectives of business. This is the only way to make it a board issue and to effectively prioritise and attempt to manage it.

Be part of the Stakeholder Intelligence community